Research is an exciting adventure, learning about how and why things work, how an idea developed, why historic events happened, and other fascinating information. Yet, many of the materials written to explain these issues are challenging to read, and listening to someone explain the same ideas is mind-boggling. There are skills you can develop to help understand new and challenging information, such as taking notes and advanced reading skills.

I. Taking notes.

When listening to a professor lecture, or your boss giving directions, how do you remember the details? Most people remember the basic idea, but need help to understand and remember the fine points that are often important. First, consider how you learn. People have several senses to absorb information that is compiled and sorted in the brain. Using this information frequently after it is acquired helps keep that idea easily accessible, so the more you use it, the stronger your memory and understanding of that idea. Recording this information in a variety of formats also helps to present that information to your brain in several ways, which also increases your memory and understanding. So, if you hear something once and never repeat it, it will be buried deeper than if you express the idea to someone else or in writing. Each time you bring that idea to the surface and express it in any format (orally, written, demonstration, etc.), you strengthen your understanding and memory of the concept. Notes are a system to write new ideas and organize them so that you can recall them readily.

Notes also provide a venue for a listener or reader to converse with the author of the idea. As you write the ideas presented, you may have questions to ask or comments to share about the concept, include a place for these additional tidbits. Ballenger (2012) shared, notes are useful to have a dialog with an author or presenter, and are often the foundation of research. So, converse with the author with questions and comments about what is shared in your notes.

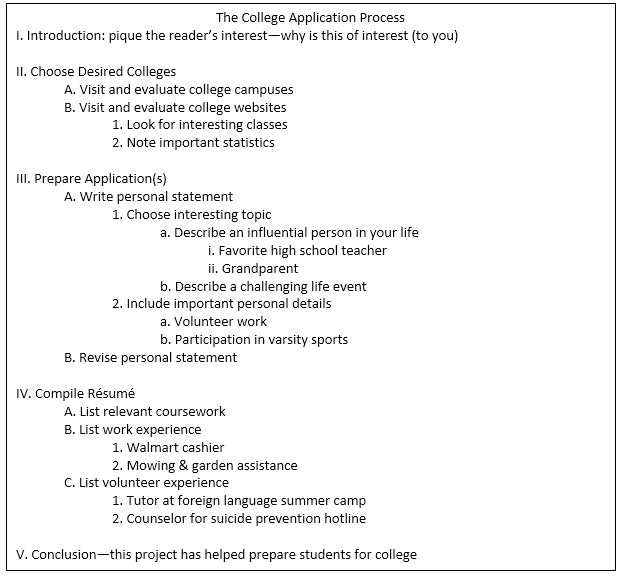

There are several recommended styles of taking notes, and for many years teachers required notes to be in a specific format. However, everyone learns differently, and learners need to feel comfortable taking notes in a style that works for them. Many generations were taught to outline each chapter read for a class, and to take notes from lectures in outline format. Outlines use headings and supporting ideas are numbered with a hierarchy of styles, denoting a specific order to the information. Outlines are useful when the information is already well-organized, such as a printed text, but taking notes in outline format for an oral or artistic presentation is difficult, since the reader does not have the headings, or a sense of order and hierarchy of ideas before the presentation.

a. Outline Format

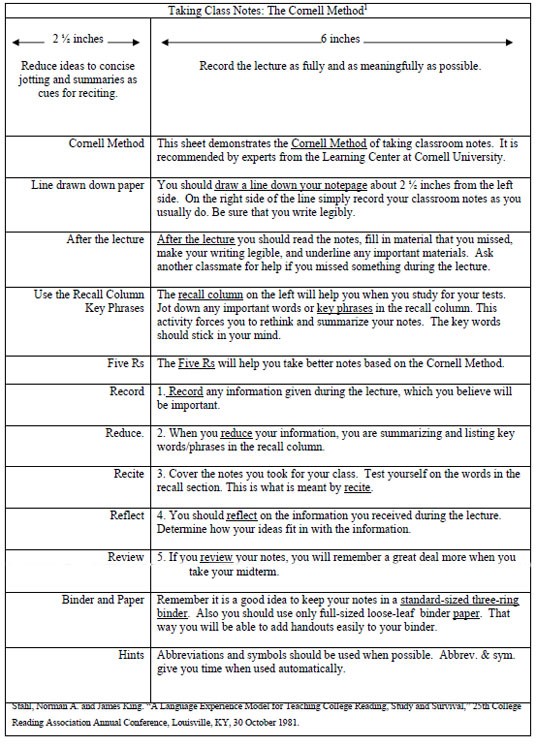

b. Cornell Note-Taking System

For many years, the Cornell Method was taught in schools, and an example is provided below. On a standard 8 ½” x 11” paper, the student would draw a vertical line 2 ½” from the left margin, making two columns. The left column is for vocabulary and key ideas, and the right column is for the corresponding explanation. Occasionally, there may be blank space on the left, depending on the amount of text to provide the level of detail necessary for a thorough understanding. At the bottom of each page, use 2-3 lines to summarize the main ideas for that section.

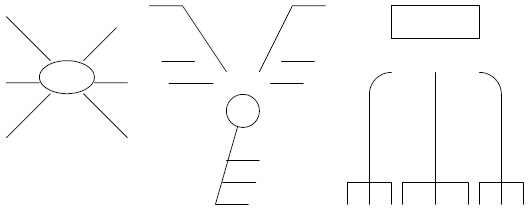

c. Idea Map or Spider graph Sample

A format often preferred by visual learners is the idea map or spider graph. The main idea is at the center, and supporting ideas are connected with lines to the main idea for each topic. With an idea map, the focus is on how the various elements are related, such as subdivisions, supporting concepts, etc.

Maps are not restricted to any one pattern, but can be formed in a variety of creative shapes as the following diagrams illustrate:

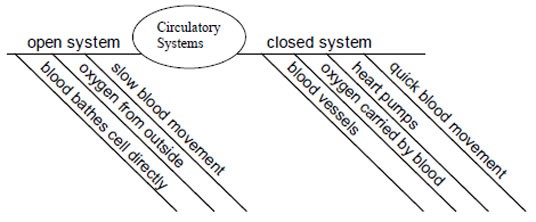

The following diagram illustrates how the lecture on the circulatory system might be mapped. Notice how the visual display emphasizes the groups of ideas supporting the topic.

Many students combine elements from each of these methods to create their own style. No matter what style you use, there are several tips to help you notes work for you. First, make sure you leave white space on every page to add details you discover were omitted as you wrote the original notes. Crowding each page with details leaves no room for questions and clarification you discover when you review them, so leave space for questions and the answers you need to understand your notes at the same level or better than when the information was introduced. Secondly, make sure you review your notes on a daily basis to make sure the concepts are clear and accessible in your memory. As you review, add the questions and details you left room for originally. Thirdly, express the ideas and concepts in writing, orally or demonstrate them with props each time you review. Many students find reviewing their notes with a study partner helps with this process, since there is someone to listen to their explanation that can notice gaps and inaccuracies, raise questions and together the students refine their understanding of the material.

In summary, make sure your notes explain the material in a manner that you, the student can understand and refer to anytime for a review of the concepts. Use abbreviations, symbols and phrases that make sense to you, and write the information in a style that makes sense to you. Grammar, punctuation, capitalization should not be a concern, rather focus on recording the main ideas presented by the author or speaker, knowing that you will review them later and fill in the details. Many students may ask to use your notes if they miss class, and they may not be able to understand your notes, which is understandable if you wrote them in your personal style. Each student needs to take notes in their own style, focusing on the main ideas.

In many situations, notes are useful to prepare for tests that may happen a month or two later, and students need to refer to material that has been buried with more recent content. Make sure that the notes taken are understood clearly over time. You might even make a “clean copy” at the end of each semester, so you can review them if you have classes that build on the information presented, or comprehensive exams that are often part of graduation requirements.

Many students understand each of these steps, but don’t know what to put in their notes. Much of the information presented is material already known, and the student does not want to make the effort or use the paper to write down material they already know. This often leads to frustration for the instructor as well, because the instructor is using the introductory material to lay a foundation essential to the understanding of future concepts. The general guideline for students is to know that information is presented for a purpose, and students need to understand all of the material presented. A student’s choice to not include elementary material may prove detrimental to the understanding of more advanced concepts. If material appears to be “too basic” to be included in notes, at least include a simple reference to the idea presented. This can be helpful when reviewing with a partner as well, especially if that partner has questions about the concept.

Taking Notes Video

II. Reading Challenging Material

Often material presented to students, either in class, reading textbooks, or research materials is advanced or more in-depth than their current understanding. This leads to frustration and anxiety, and the student feels inadequate to pursue the material. The student needs to keep in mind that the purpose of an education is to expand their knowledge, and often will include advanced material. So, when dealing with advanced or new information, recognize the material is new! College classes will be presenting material in a manner that will challenge students to learn the information with an in-depth level, preparing for more in-depth understanding that contributes to their professional training. Instructors expect students to be challenged in their classes, and students should be challenged reading advanced material!

After you recognize that the material is in-depth, prepare yourself, and recognize that you probably will not understand all the information the first time. When you open a text, first look at the table of contents, and note the progression of concepts that are introduced. Does the first chapter lay a foundation for future information? If you skip to the chapter you need, will you be able to understand it? Many times students omit the readings early in the semester, because they understand the lectures. However, the material presented early in the text may be important to the comprehension of future sections.

When you have difficult material to read, read each section or paragraph in steps, to more fully understand the concepts. First, survey the section, by briefly reading the headings, subheadings, note the graphics, sidebars and key terms in bold or italics. Question the author on the message or intent of the material. You may find the author has included questions at the end, which should be helpful. This “survey and question” process should help you to mentally prepare for the new information. Similar to looking at a map before taking a trip, the headings prepare your mind for the new avenues and territory to be covered. If you do not have an idea where you are going, you are often lost!

The next step is to read the material, knowing that much of it may be confusing or unclear. As you read, if you become overwhelmed or confused, take a brief pause (30-60 seconds) and look away, giving your brain a chance to absorb the ideas you have just encountered. Then return to reading, pausing briefly when overwhelmed.

After reading the first section, get a pen/pencil and reread it, this time marking phrases or sections, or include the key ideas in your notes on separate paper. Use symbols or highlighting to mark portions, such as the following:

? seems unclear; need help in understanding the ideas presented or practice the application

* important idea!

# key detail/supporting information

Use other symbols as necessary, but make sure to not write over the text, which makes it difficult to read. Note: if the printed work is not your personal copy, make these notes on separate paper. Don’t damage borrowed property!

After rereading and marking the section with symbols, reread the material again, and anticipate understanding at least the basic ideas. During this reading, write questions in the margins or in your notes as you go. Reread the section a fourth time, trying to answer the questions you wrote previously. Note that you may need to reread the section three or four times, to fully absorb the information. However, if there are concepts that continue to be unclear, consult with your instructor. Instructors are usually willing to work with a student that has made a significant effort to learn new material. Conversely, students need to make that significant effort before expecting help from instructors.

The final step is to recite the material, either in written notes, oral expression or use the information in a practical application. Before continuing on to the next section of readings, review the section again. Remember, the author may refer to concepts introduced in this section, and your understanding is key to understanding future material. The SQ3R method was developed by Francis P. Robinson to assist college students when reading texts and advanced sources of information.